Electromagnetic Field 2024

a non-profit camping festival for those with an inquisitive mind or an interest in making things: hackers, artists, geeks, crafters, scientists, and engineers.

It’s also been described as the “special interest haver convention” and “Glastonbury for geeks”

It always sounded very appealing to me, except for the camping part.

My memories of camping from school are of lugging heavy equipment around damp lanes in Wales, setting up a tent in a field full of sheep droppings (sometimes cow, but usually sheep), and waking up in the rain even wetter than I’d gone to sleep. So whilst in theory I love the idea of sleeping out under the open sky, and of the self-reliance of carrying your own shelter, in practice I found it miserable.

I could have rented a camper van, I suppose, but I don’t much relish the idea of driving a large van across the country.

Nonetheless, there was still a thought in my mind that perhaps camping could be enjoyable. Thirty years have elapsed since I last tried it. Modern tents are lighter and more waterproof, for a start. And I wouldn’t be marching 10 km a day between stops.

I missed the first two ticket releases for EMF, but when some extra tickets became available, I decided it was time to give it a try.

And so I ended up in a field in Herefordshire for four nights.

I had a fantastic time. The weather held up, although the whole site was quite damp from heavy rain in the preceding days.

Art, tents, flags

I thought I had camped on level ground, but it wasn’t quite level, and I tended to roll to one side in my sleep. Maybe I need to use a spirit level next time.

My nominally two-person tent from Decathlon was a comfortable size for one person. I was very glad that I bought the blackout version: it was nice not to be woken by the sun at four o’clock. At 3 kg, I wouldn’t want to carry it around on a trek, but it was an ideal festival tent for a solo camper.

I’ve been to one-day festivals before, and they can be quite a slog. I was glad to have a private cocoon to escape to for a break or an afternoon nap. That’s a point in favour of camping.

It was much colder at night than I had anticipated. I didn’t bring my warm puffy jacket, because I thought it was unnecessary, but I wished I had. My sleeping bag wasn’t comfortable down in the single-digit (celsius) temperatures that we experienced on a couple of nights, and I woke in the night feeling chilled to my bones. On Sunday morning, my nose was so cold than condensation had formed on it, although Sunday itself turned out to be the hottest day of the festival by far.

Sunset

I was lucky enough to get tickets to a couple of workshops:

- Building a sensor.community air quality monitoring device

- Processing and analysing bat recordings

- Building a π•pistrelle bat listening and recording device

I didn’t spend all that much time in talks, though, because there was so much else going on to see and do. My favourite parts of the festival were the ones that happened at random:

-

On Friday afternoon, as I strolled along with a pint of cider in my hand (when in the west …), I chanced upon a tent full of people singing sea shanties. Of course, I joined in.

-

I overheard someone talking about an acoustic jam session, they added me to a chat group, and when someone posted that they were “about to head down to the side of the lake with the banjo for a few hours, maybe see some of you there”, I went down with my mandolin for what turned into an enjoyable few hours with a couple of banjos, another (octave) mandolin, some guitars, a recorder, and a fiddle.

-

I camped with other people from the South London Makerspace, and we put on a free breakfast every morning for anyone who wanted it. It was supposed to be an hour from 08:30 to 09:30, but I found myself there every day until at least 11:00, chatting with anyone who came by.

But talking about events doesn’t really tell you what the festival was like.

It was (at least to me) the safest, most socially cohesive environment I’ve experienced. I didn’t worry about theft or violence. It felt like at least a quarter of the people there were, in one way or another, to varying extents, not confirming with their assigned birth gender, and appeared to feel safe and comfortable in doing so. The trans pride flag might have been the flag most frequently flown. It was strange to step back into the outside world afterwards.

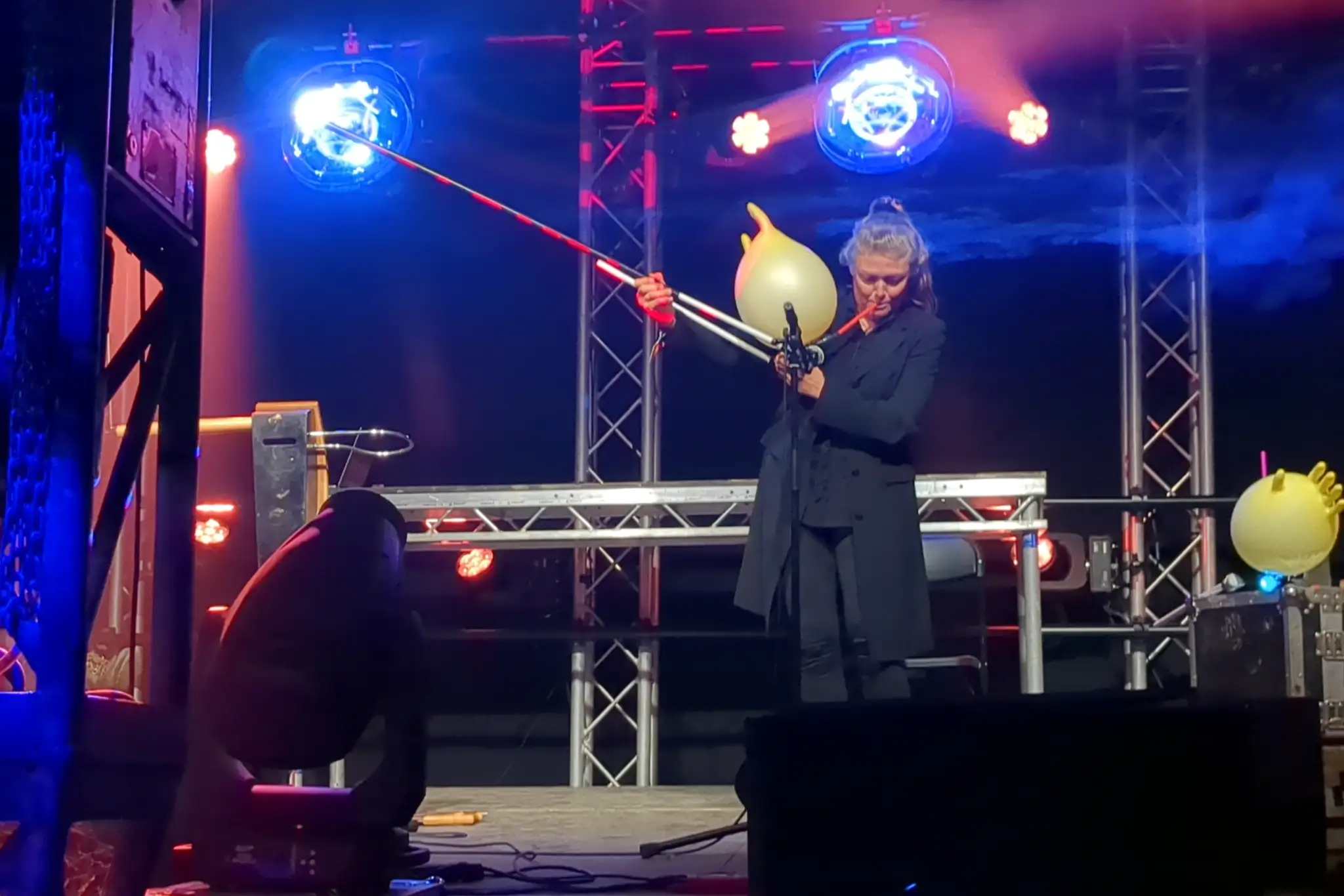

Karina Townsend playing DIY rubber glove bagpipes

I danced until 2 a.m. at Null Sector, an open-air club made of shipping containers and flamethrowers, and playing extremely loud “sounds wholly or predominantly characterized by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”. (Earplugs were available; I had my own.)

I learned a new phrase, “orphan source”:

An orphan source is a self-contained radioactive source that is no longer under regulatory control.

Someone left a number of devices containing Americium-241 at the swap shop. Someone else recognised the risk, and they had to find out how many had been left, and to recover them all for safe disposal. The devices were safe unless disassembled, and the situation was eventually resolved.

I avoided sunburn thanks to a hat, a scarf, and the scrupulous application of sunscreen.

Most nostalgic moment of the festival: when the DJ dropped a remix of Ayumi Hamasaki’s 1999 hit Boys & Girls in Null Sector on Friday night. This came out in Japan the year I first went there as a young exchange student, and was a huge hit. I must have heard it at least once a day during that year.

By the end, I felt a pang of loss as I looked at the rectangle of grass where my tent had been. After a couple of months of not being able to live in my own house while it’s being renovated, it was the closest I’ve had to my own home in weeks.

I hope I’ll go again next time, in 2026, and I’ll be better prepared.